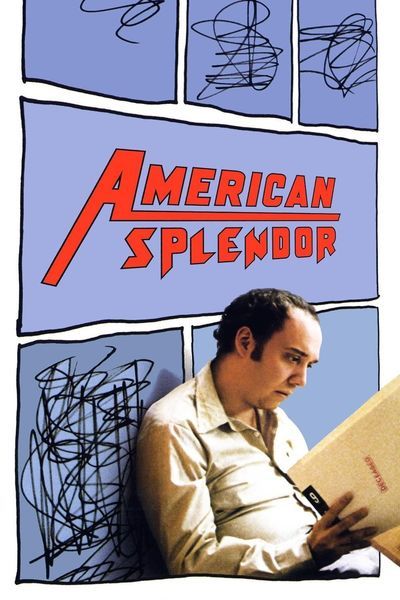

American Splendor

101 min | 35mm

One of the closing shots of “American Splendor” shows a retirement party for Harvey Pekar, who is ending his career as a file clerk at a V.A. hospital in Cleveland. This is a real party, and it is a real retirement. Harvey Pekar, the star of comic books, the Letterman show and now this movie, worked all of his life as a file clerk. When I met Harvey and his wife, Joyce Brabner, at Cannes 2003, she told me: “He's grade G-4. Grade G-2 is minimum wage. Isn’t that something, after 30 years as a file clerk?” Yes, but it got them to Cannes. Pekar is one of the heroes of graphic novels, which are comic books with a yearning toward the light. He had the good fortune to meet the legendary comic artist R. Crumb in the 1970s. He observed with his usual sour pessimism that comics were never written about people like him, and as he talked, a light bulb all but appeared above Crumb’s head, and the comic book “American Splendor” was born, with Pekar as writer and Crumb as illustrator.

The books chronicle the life of a man very much indeed like Harvey Pekar. He works at a thankless job. He has friends at work, like the “world-class nerd” Toby Radloff, who share his complaints, although not at the Pekarian level of existential misery. The comic book brings him a visit from a fan named Joyce Brabner, who turns out improbably to be able to comprehend his existence while insisting on her own, and eventually they gain a daughter, Danielle Batone, sort of through osmosis (the daughter of a friend, she comes to visit, and decides to stay). The books follow Harvey, Joyce and Danielle as they sail through life, not omitting “Our Cancer Year,” a book retelling his travails after Harvey finds a lump on a testicle.

The comics are true, deep and funny precisely because they see that we are all superheroes doing daily battle against twisted and perverted villains. We have secret powers others do not suspect. We have secret identities. Our enemies may not be as colorful as the Joker or Dr. Evil, but certainly they are malevolent—who could be more hateful, for example, than an anal-retentive supervisor, an incompetent medical orderly, a greedy landlord? When Harvey fills with rage, only the graphics set him aside from the Hulk.

The peculiarity and genius of “American Splendor” was always that true life and fiction marched hand in hand. There was a real Harvey Pekar, who looked very much like the one in the comic book, and whose own life was being described. Now comes this magnificently audacious movie, in which fact and fiction sometimes coexist in the same frame. We see and hear the real Harvey Pekar, and then his story is played by the actor Paul Giamatti, sometimes with Harvey commenting on “this guy who is playing me.” We see the real Joyce Brabner, and we see Hope Davis playing her. We concede that Giamatti and Davis have mastered not only the looks but the feels and even the souls of these two people, and then there is Judah Friedlander to play Toby Radloff, who we might think could not be played by anybody, but there the two Tobys are, and we can see it’s a match.

The movie deals not merely with real and fictional characters, but even with levels of presentation. There are documentary scenes, fictional scenes and then scenes illustrated and developed as comic books, with the drawings sometimes segueing into reality or back again. The filmmakers have taken the challenge of filming a comic book based on a life, and turned it into an advantage—the movie is mesmerizing in the way it lures us into the daily hopes and fears of this Cleveland family.

The personality of the real Harvey Pekar is central to the success of everything. Not any file clerk would have done. Pekar’s genius is to see his life from the outside, as a life like all lives, in which eventual tragedy is given a daily reprieve. He is brutally honest. The conversations he has with Joyce are conversations like those we really have. We don’t fight over trivial things, because nothing worth fighting over is trivial. As Harvey might say, Hey, it’s important to me! The Letterman sequences have the fascination of an approaching train wreck. Pekar really was a regular on the program in the 1980s, where he did not change in the slightest degree from the real Harvey. He gave as good as he got, until his resentments, angers and grudges led him to question the fundamental realities of the show itself, and then he was bounced. We see real Letterman footage, and then a fictional re-creation of Pekar’s final show. Letterman is not a bad guy, but he has a show to do, and Pekar is a good guest following his own agenda up to a point, but then he goes far, far beyond that point. When I talked with Pekar at Cannes, he confided that after Letterman essentially fired him and went to a commercial break, Dave leaned over and whispered into Harvey’s ear: “You blew a good thing.” Well, he did. But blowing a good thing is Harvey’s fate in life, just as stumbling upon a good thing is his victory. What we get in both cases is the unmistakable sense that Pekar does nothing for effect, that all of his decisions and responses proceed from some limitless well of absolute certitude. What we also discover is that Harvey is not entirely a dyspeptic grump, but has sweetness and hope waving desperately from somewhere deep within his despair.

This film is delightful in the way it finds its own way to tell its own story. There was no model to draw on, but Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini, who wrote and directed it, have made a great film by trusting to Pekar’s artistic credo, which amounts to: What you see is what you get. The casting of Giamatti and Davis is perfect, but of course it had to be, or the whole enterprise would have collapsed. Giamatti is not a million miles away from other characters he has played, in movies such as “Storytelling,” “Private Parts” and “Man on the Moon,” but Davis achieves an uncanny transformation. I saw her again recently in “The Secret Lives of Dentists,” playing a dentist, wife and mother with no points in common with Joyce Brabner—not in look, not in style, not in identity. Now here she is as Joyce. I’ve met Joyce Brabner, and she’s Joyce Brabner.

Movies like this seem to come out of nowhere, like free-standing miracles. But “American Splendor” does have a source, and its source is Harvey Pekar himself—his life, and what he has made of it. The guy is the real thing. He found Joyce, who is also the real thing, and Danielle found them, and as I talked with her I could see she was the real thing, too. She wants to go into showbiz, she told me, but she doesn’t want to be an actress, because then she might be unemployable after 40. She said she wants to work behind the scenes. More longevity that way. Harvey nodded approvingly. Go for the pension.