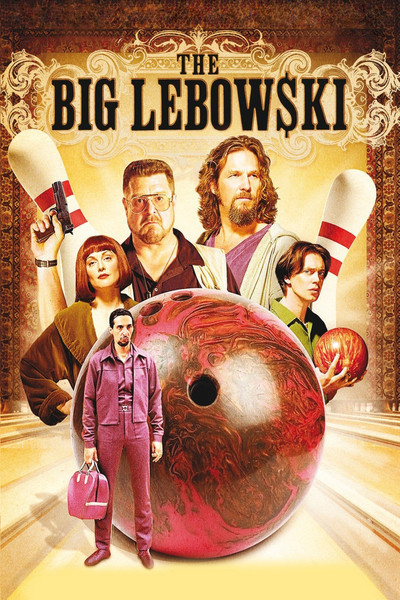

The Big Lebowski

117 min | 35mm

The Coen brothers’ “The Big Lebowski'” is a genial, shambling comedy about a human train wreck, and should come with a warning like the one Mark Twain attached to “Huckleberry Finn”: “Persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.'” It’s about a man named Jeff Lebowski, who calls himself the Dude, and is described by the narrator as “the laziest man in Los Angeles County.” He lives only to go bowling, but is mistaken for a millionaire named the Big Lebowski, with dire consequences.

This is the first movie by Joel and Ethan Coen since “Fargo.” Few movies could equal that one, and this one doesn’t—but it’s weirdly engaging, like its hero. The Dude is played by Jeff Bridges with a goatee, a potbelly, a ponytail and a pair of Bermuda shorts so large they may have been borrowed from his best friend and bowling teammate, Walter Sobchak (John Goodman). Their other teammate is Donny (Steve Buscemi), who may not be very bright, but it’s hard be sure since he never is allowed to complete a sentence.

Everybody knows somebody like the Dude—and so, rumor has it, do the Coen brothers. They based the character on a movie producer and distributor named Jeff Dowd, a familiar figure at film festivals, who is tall, large, shaggy and aboil with enthusiasm. Dowd is much more successful than Lebowski (he has played an important role in the Coens’ careers as indie filmmakers), but no less a creature of the moment. Both dudes depend on improvisation and inspiration much more than organization.

In spirit, “The Big Lebowski” resembles the Coens’ “Raising Arizona,” with its large cast of peculiar characters and its strangely wonderful dialogue. Here, in a film set at the time of the Gulf War, are characters whose speech was shaped by earlier times: Vietnam (Walter), the flower power era (the Dude) and “Twilight Zone” (Donny). Their very notion of reality may be shaped by the limited ways they have to describe it. One of the pleasures of “Fargo” was the way the Coens listened carefully to how their characters spoke. Here, too, note that when the In-N-Out Burger shop is suggested for a rendezvous, the Dude supplies its address: That’s the sort of precise information he would possess.

As the film opens, the Dude is visited by two enforcers for a porn king (Ben Gazzara) who is owed a lot of money by the Big Lebowski’s wife. The goons of course have the wrong Lebowski, but before they figure that out, one already has urinated on the Dude’s rug, causing deep enmity: “That rug really tied the room together,” the Dude mourns. Walter, the Viet vet, leads the charge for revenge.

Borrowing lines directly from President George H.W. Bush on TV, he vows that “this aggression will not stand” and urges the Dude to “draw a line in the sand.” The Dude visits the other Lebowski (David Huddleston), leaves with one of his rugs and soon finds himself enlisted in the millionaire’s schemes. The rich Lebowski, in a wheelchair and gazing into a fireplace like Maj. Amberson in “The Magnificent Ambersons,” tells the Dude that his wife, Bunny (Tara Reid), has been kidnapped. He wants the Dude to deliver the ransom money. This plan is opposed by Maude (Julianne Moore), the Big Lebowski’s daughter from an earlier marriage. Moore, who played a porno actress in “Boogie Nights,” here plays an altogether different kind of erotic artist; she covers her body with paint and hurls herself through the air in a leather harness.

Los Angeles in this film is a zoo of peculiar characters. One of the funniest is a Latino bowler named Jesus (John Turturro), who is seen going door to door in his neighborhood on the sort of mission you read about, but never picture anyone actually performing. The Dude tends to have colorful hallucinations when he’s socked in the jaw or pounded on the head, which happens often, and one of them involves a musical comedy sequence inspired by Busby Berkeley. (It includes the first point-of-view shot in history from inside a bowling ball.) Some may complain “The Big Lebowski” rushes in all directions and never ends up anywhere. That isn’t the film’s flaw, but its style. The Dude, who smokes a lot of pot and guzzles White Russians made with half-and-half, starts every day filled with resolve, but his plans gradually dissolve into a haze of missed opportunities and missed intentions. Most people lead lives with a third act. The Dude lives days without evenings. The spirit is established right at the outset, when the narrator (Sam Elliott) starts out well enough, but eventually confesses he’s lost his train of thought.