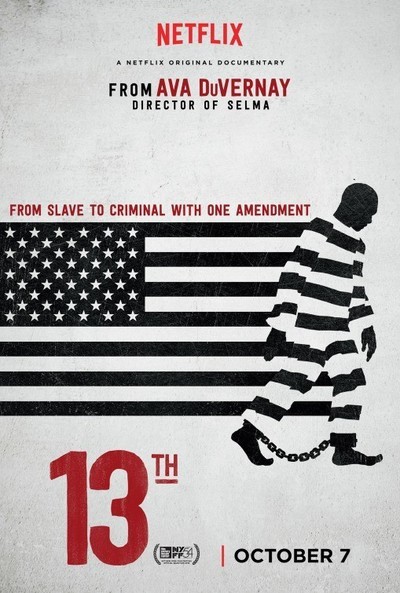

13th

100 min | DCP

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

— 13th Amendment of the United States Constitution

When the 13th Amendment was ratified in 1865, its drafters left themselves a large, very exploitable loophole in the guise of an easily missed clause in its definition. That clause, which converts slavery from a legal business model to an equally legal method of punishment for criminals, is the subject of the Netflix documentary “13th.” Director Ava DuVernay takes an unflinching, well-informed and thoroughly researched look at the American system of incarceration, specifically how the prison industrial complex affects people of color. Her analysis could not be more timely nor more infuriating. The film builds its case piece by shattering piece, inspiring levels of shock and outrage that stun the viewer, leaving one shaken and disturbed before closing out on a visual note of hope designed to keep us on the hook as advocates for change.

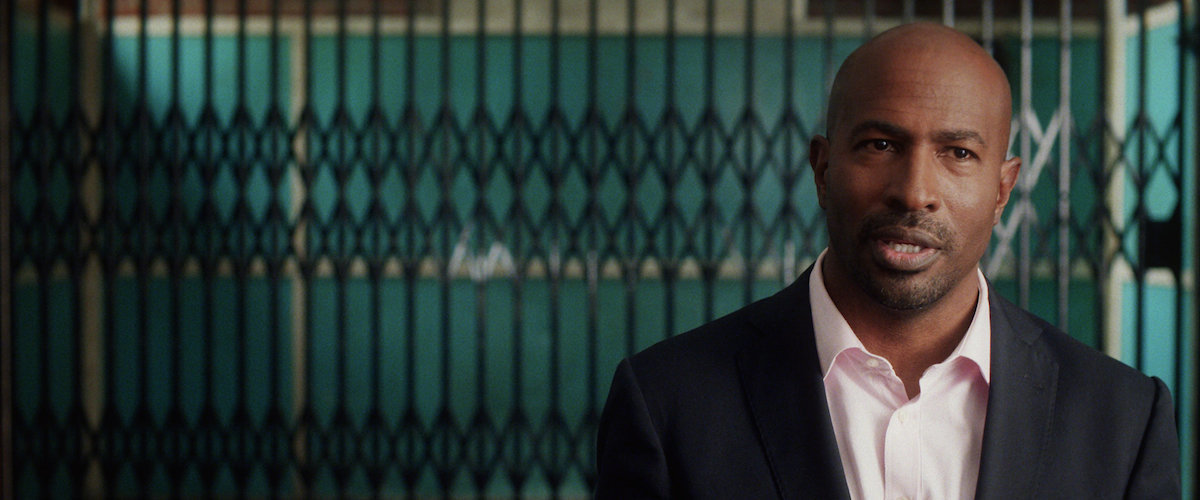

“13th” begins with an alarming statistic: One out of four African-American males will serve prison time at one point or another in their lives. Our journey begins from there, with a slew of familiar and occasionally surprising talking heads filling the frame and providing information. DuVernay not only interviews liberal scholars and activists for the cause like Angela Davis, Henry Louis Gates and Van Jones, she also devotes screen time to conservatives such as Newt Gingrich and Grover Norquist. Each interviewee is shot in a location that evokes an industrial setting, which visually supports the theme of prison as a factory churning out the free labor that the 13th Amendment supposedly dismantled when it abolished slavery.

We’re told that, after the Civil War, the economy of the former Confederate States of America was decimated. Their primary source of income, slaves, was no longer obligated to line Southerners’ pockets with their blood, sweat and tears. Unless, of course, they were criminals. “Except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted” reads the loophole in the law. In the first iteration of a “Southern strategy,” hundreds of newly emancipated slaves were re-enlisted into free, legal servitude courtesy of minor or trumped-up charges. The duly convicted part may have been questionable, but by no means did it need to be justifiably proven.

So begins a cycle that DuVernay examines in each of its evolving iterations; when one method of subservience-based terror falls out of favor, another takes its place. The list feels endless and includes lynching, Jim Crow, Nixon’s presidential campaign, Reagan’s war on drugs, Bill Clinton’s three strikes and mandatory sentencing laws and the current cash-for-prisoners model that generates millions for private bail and incarceration firms.

That last item is a major point of discussion in “13th,” with an onscreen graphic keeping tally of the number of prisoners in the system as the years pass. Starting in the 1940s, the curve of the prisoner count graph begins rising slowly though steeply. A meteoric rise began during the civil rights movement and continued into the current day. As this statistic rises, so does the level of decimation of families of color. The stronger the protest for rights, the harder the system fights back against it with means of incarceration. Profit becomes the major byproduct of this cycle, with an organization called ALEC providing a scary, sinister influence on building laws that make its corporate members richer.

Several times throughout “13th” there is a shock cut to the word “criminal,” which stands alone against a black background and is centered on the huge movie screen. It serves as a reminder that far too often, people of color are seen as simply that, regardless of who they are. Starting with D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation,” DuVernay traces the myth of the scary black felon with supernatural levels of strength and deviant sexual potency, a myth designed to terrify the majority into believing that only white people were truly human and deserving of proper treatment. This dehumanization allowed for the acceptance of laws and ideas that had more than a hint of bias. We see higher sentences given for crack vs. cocaine possession and plea bargains accepted by innocent people too terrified to go to trial. We also learn that a troubling percentage of people remain in jail because they’re too poor to post their own bail. And regardless of your color, if you’re a felon, you can no longer vote to change the laws that may have unfairly prosecuted you. You lose a primary right all Americans have.

“13th” covers a lot of ground as it works its way to the current days of Black Lives Matter and the terrifying videos of the endless list of African-Americans being shot by police or folks who supposedly “stood their ground.” On her journey to this point, DuVernay doesn’t let either political party off the hook, nor does she ignore the fact that many people of color bought into the law-and-order philosophies that led to the current situation. We see Hillary Clinton talking about “super-predators” and Donald Trump’s full-page ad advocating the death penalty for the Central Park Five (who, as a reminder, were all innocent). We also see people like African-American congressman Charlie Rangel, who originally was on board with the tough-on-crime laws President Clinton signed into law.

By the time we get to the montage of the deaths of Philando Castile, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner and others (not to mention the huge, screen-covering graphic of names of African-Americans shot by law enforcement), “13th” has already proven its thesis on how such events can not only occur, but can also seem sadly like “business as usual.” It’s a devastating finale to the film, one that follows an onscreen discussion about whether or not the destruction of black bodies should be run ad nauseum on cable news programs. DuVernay opts to show the footage, with an onscreen disclaimer that it’s being shown with permission by the families of the victims, something she did not need to seek but did so out of respect.

Between the lines, “13th” boldly asks the question if African-Americans were actually ever truly “free” in this country. We are freer, as this generation has it a lot easier than our ancestors who were enslaved, but the question of being as completely “free” as our white compatriots hangs in the air. If not, will the day come when all things will be equal? The final takeaway of “13th” is that change must come not from politicians, but from the hearts and minds of the American people.

Despite the heavy subject matter, DuVernay ends the film with joyful scenes of children and adults of color enjoying themselves in a variety of activities. It reminds us, as she said in her Q&A with New York Film Festival director Kent Jones, that “Black trauma is not our entire lives. There is also black joy.” That inspiring message, and all the important, educational information provided by this excellent documentary, make “13th” a must-see.